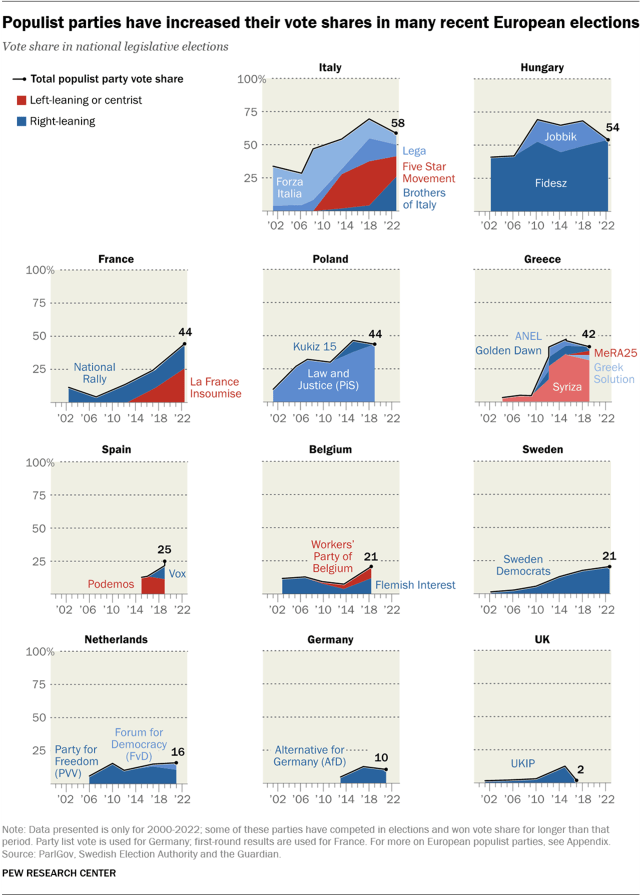

Recent elections in Italy and Sweden have been resounding successes for right-wing populist parties, underscoring the growing electoral strength that such parties have displayed in Europe in recent years.

In Italy, the right-wing populist Brothers of Italy party secured the highest vote share of any single party in the nation’s recent election, making its leader, Giorgia Meloni, the likely prime minister. In Sweden, the Sweden Democrats emerged as the second-most popular party in the country’s recent election. Their strong performance is the culmination of steady growth over the last six parliamentary elections and the near doubling of their vote share since the 2014 election.

Across Europe, populists – especially those on the ideological right – have been winning larger shares of the vote in recent legislative elections, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data drawn primarily from Parlgov, a clearinghouse for cross-national political information. The Center defines populists on the basis of three academic measures and classifies them as right- or left-leaning based on expert evaluations of their ideology. (For more on these definitions, see “How we did this” or the appendix.)

This Pew Research Center analysis examines the growing electoral strength of populist political parties in 11 European countries. Vote share data is drawn from Parlgov for all elections except the most recent Swedish and Italian elections, where we consulted country-specific vote returns.

We use three measures to classify populist parties: anti-elite ratings from the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), Norris’ Global Party Survey (GPS) and The PopuList. We define a party as populist when at least two of these three measures classify it as such. For more information on how we classify European populist parties, read the appendix. Not all populist parties were asked about on the 2022 Global Attitudes survey, so results in the second table about favorability only include the parties that respondents were asked about.

Because the 2011 and 2014 CHES surveys do not include all relevant variables for our definition of populism, we focus our analysis on the 2019 CHES and 2019 GPS. As a result, the parties included in this analysis may be biased in favor of those that remain electorally significant. Similarly, The PopuList specifically looks at parties that “obtained at least 2% of the vote in at least one national parliamentary election since 1998” and thus parties that were a larger share of the vote prior to 1998 may not be included. Additionally, parties may exist that are considered “far-right” or “far-left” but not populist, according to our working definition; those are not included here. The ideology of parties may also have shifted over time; we classify parties as left, right or center on the basis of CHES experts in 2019.

All European countries are not included in this analysis because we focus only on the 11 countries in Europe that were surveyed in 2022. Surveys were all conducted with nationally representative populations and were fielded from Feb. 14 to June 3, 2022, over the phone with adults in Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Surveys were conducted face to face in Hungary and Poland.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

In Italy this year, for example, around four-in-ten voters cast their ballots for one of the three major right-wing populist parties: Brothers of Italy, Forza Italia and Lega, up from around a third who did the same in 2018 and around three-in-ten in 2013. On the other hand, Five Star, a centrist populist party, saw its vote share fall by roughly half since 2018, when it governed as part of a populist coalition with Lega.

In Spain, the share of the vote going to populist parties roughly doubled between 2015 and 2019 – when the country’s most recent legislative election took place – rising from around 13% to around 25%. This was especially the case among populists on the right, with the Vox party seeing its vote share grow from around 10% to around 15% during that span.

In the Netherlands, right-leaning populist parties garnered around 16% of the vote in 2021 – a high not seen in nearly a decade of parliamentary elections.

In both Hungary and Poland, right-wing populist parties have surged to power, making enormous gains in the last two decades. In Hungary, President Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party, which has been in power since 2010, secured a supermajority in this year’s legislative elections – though the total share voting for populist parties in the country fell slightly as Jobbik, another right-wing populist group, joined an anti-Fidesz coalition. In Poland, the ruling Law and Justice Party (Pis) roughly quadrupled their vote share between 2001 and 2019, from around one-in-ten votes to around four-in-ten.

In Belgium and France, while the overall share of voters supporting populist parties has grown substantially in recent years, there have been gains for both right- and left-leaning populist parties. The right-leaning Flemish Interest party won around 12% of Belgium’s vote in 2019, marking one of its most successful elections since 2007. But the left-leaning Worker’s Party of Belgium has also been ascendent, winning around 9% of the vote in 2019, up from less than 1% in 2007.

In France, the share of voters casting first-round ballots for a populist party has risen from around 10% in the 1980s to around 44% as of the 2022 election. On the right, the National Rally party – previously called National Front – has steadily increased its vote share in parliamentary elections since 2007 and, under Marine LePen’s leadership, became one of two parties in the second round of the last two presidential elections. La France Insoumise, a populist party on the left, garnered around a quarter of the first-round parliamentary bloc in 2022 – though it did so as part of a far-left bloc alongside the Socialist Party, the Greens and the French Communist Party (these four parties running separately in the previous election also garnered around a quarter of the vote).

Not all populist parties are on the rise

Germany and Greece somewhat buck the trend. In Germany, support for the right-leaning Alternative for Germany (AfD) fell nationally in the country’s most recent election in 2021, knocking it from its claim as the largest opposition party and the third-biggest party overall, though it remains a force in eastern Germany.

And in Greece, while populist parties still garner a large share of the vote, their popularity has been falling slightly in recent years. Left-leaning Syriza is significantly more popular there than right-leaning parties, including Greek Solution and Golden Dawn.

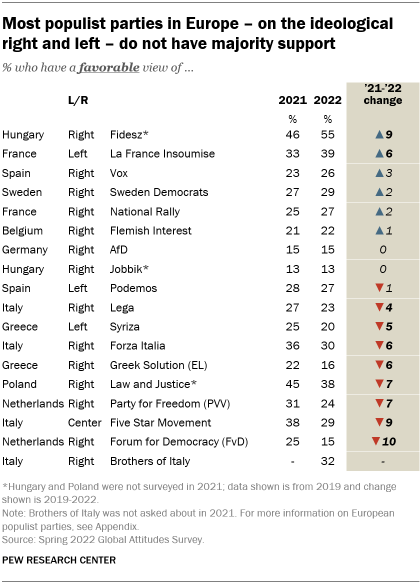

Despite their electoral gains in many countries, most populist political parties in Europe – on the right and left – are broadly unpopular, according to Pew Research Center surveys. In fact, outside of Hungary, where the ruling right-populist party Fidesz is seen favorably by 55% of the public, no party receives favorable ratings from a majority of the public.

Still, being seen in a positive light is not a prerequisite for electoral success, as Italy shows. There, only around a third of Italians saw Brothers of Italy (32%), Forza Italia (30%) or Five Star (29%) favorably when the Center surveyed the country this past spring – and even fewer said the same of Lega (23%). The share of Italians with a positive view of some of these parties had even fallen since 2020. Nonetheless, record low turnout in Italy and the limited popularity of other parties, including the Democratic Party (38% in 2022, down from 42% in 2021), was enough to catapult the populist coalition to victory.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, its methodology, an appendix detailing how populist parties are defined, and the full dataset.